By Wira A. Swadana, Ellen Risfenti, and Carolina Astri, Researchers of WRI Indonesia

Indonesia's archipelago is a natural powerhouse, harboring 17 percent of the world's mangrove and seagrass ecosystems. This immense "blue carbon" store is critical for global climate mitigation, with mangroves alone estimated to absorb over 122.2 million tonnes of CO2 annually. This rich blue ecosystem, Indonesia's blue initiatives are deeply interconnected with the livelihoods of its coastal communities. In provinces such as Riau and West Nusa Tenggara, for example, mangroves and seagrasses generate millions of dollars in ecosystem services annually.

However, despite these vast natural benefits, economic values, and Indonesia’s blue carbon climate goals, coastal communities continue to struggle to access the financial and social resources available to them. If Indonesia's economic transition shifts toward blue initiatives, ensuring an equitable blue carbon system is essential to include those who are at the forefront of conservation as the primary beneficiaries.

As a key player in advancing global blue carbon mitigation, Indonesia is actively raising the bar to protect these ecosystems, in line with the IPCC. The National Long-Term Planning (RPJPN) 2025–2045, coordinated by the Ministry of National Development Planning, integrates blue economy strategies focused on mangrove rehabilitation and reducing emissions. Furthermore, the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries has translated Presidential Regulation No. 98/2021 on carbon pricing into Ministerial Regulation No. 1/2025 on ocean-based carbon pricing. These policy shifts reflect Indonesia's ambition, which the Just Transition (JT) concept can help fulfill in several key areas.

The United Nations describes a "Just Transition" (JT) as the process of a transition toward a low-carbon economy in a fair and equitable manner. Originating in the 1970s from labor movements, the concept emphasized advocating for those negatively affected by industrial transitions.

While historically prevalent in the energy sector, the JT in Indonesia was largely common to fossil fuel workers. The concept then has broadened to encompass four core principles: distributive justice (the fair allocation of resources and benefits within society), restorative justice (repairing previous harm through reconciliation and the active involvement of those affected), procedural justice (ensuring the fairness in decision-making processes, emphasising the importance of transparent and equitable procedures), and recognition justice (acknowledging and respecting the identities, experiences, and cultural differences of individuals and communities, ensuring that they are valued in both social and legal contexts).

The JT now encompasses broader climate action in pursuit of Net-Zero Emissions, emphasizing the importance of considering all impacted stakeholders, including workers, suppliers, communities, and consumers.

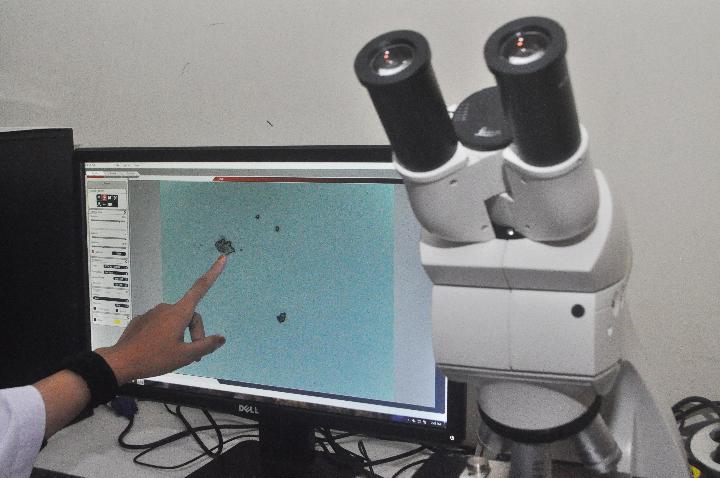

WRI Indonesia’s pilot activities in Riau and West Nusa Tenggara demonstrate that effective governance and social accountability succeed only when ocean-dependent communities are actively involved in data collection, rather than being treated as passive subjects.

Safeguards for gender equity, disability, and social inclusion (GEDSI) are especially urgent. For example, women fishers and gleaners play a vital economic role yet are frequently overlooked in fisheries and marine governance due to patriarchal and gender-based barriers, such as the dual burden of domestic work and fishing. These barriers must be overcome by engaging these vulnerable groups clearly, safeguarding them, and involving them actively in processes to maximize equitable benefits sharing.

WRI Indonesia’s early data indicate that coastal households remain highly vulnerable. The economic value of mangrove ecosystem services in Riau is approximately US$124.6 million. In Riau, seven of the eleven districts and cities have coastal areas. However, seasonal bans on toli shad fishing (known locally as trubuk) and mangrove zoning reduce the daily income of small-scale fishers and women who gather crabs and shellfish.

Meanwhile, in West Nusa Tenggara, mangroves and seagrasses generate approximately US$790 million per year, primarily from fisheries, coastal production, carbon sequestration, and tourism. However, rules limiting access to nursery grounds for snapper and grouper similarly cut household earnings. Women and youth, in particular, face limited access to assets, low participation rates, and barriers to accessing benefits.

Additionally, when revenues from carbon credits are managed at the national level or by external investors, it results in uneven benefit distribution. Procedural and recognition gaps persist when those most affected lack meaningful representation and their local knowledge is disregarded. Furthermore, the economic benefits of ecotourism and conservation branding are often attributed to operators or local government agencies rather than local households, reinforcing the distributional gap.

If Indonesia aims to harness blue carbon to benefit both the climate and its communities, policymakers must utilize the four justice tenets to inform the implementation of the JT concept. This is essential, as coastal communities currently experience poverty rates around 25 percent higher than the national average. This persistent poverty cycle could significantly hinder the country's efforts in blue carbon conservation and rehabilitation.

These observations confirm that by designing blue carbon governance with JT principles in mind, it can reduce poverty and exclusion, especially among groups typically marginalized from marine and fisheries decision-making. In current practices, however, social and economic considerations are often incorporated only later in the planning process. This minimizes benefit sharing, rather than centering social and economic aspects as integral to implementation. Applying the JT approach can lead to more meaningful and proactive engagements from all relevant stakeholders, primarily the coastal communities.

Therefore, by incorporating the JT approach, the government can encourage stakeholders to achieve more equitable and fair results, extending Indonesia's blue ecosystem ambition. A crucial initial step is to create JT guidelines and regulations that facilitate safeguards in the blue carbon sector. Furthermore, Indonesia should pilot these guidelines and regulations in a province before scaling them up nationally.

At a policy level, the government must recognize the vital role of the blue carbon sector in achieving its Net-Zero Emissions (NZE) target in climate commitment documents such as NDCs (nationally determined contributions). This recognition must be coupled with the JT framing and GEDSI integration as a non-negotiable cross-cutting safeguard. With momentum for raising climate ambition at its peak, Indonesia should prioritize significant progress on its climate documents to demonstrate the importance of a just blue carbon transition.

*) DISCLAIMER

Articles published in the “Your Views & Stories” section of en.tempo.co website are personal opinions written by third parties, and cannot be related or attributed to en.tempo.co’s official stance.

:strip_icc():format(jpeg)/kly-media-production/medias/5316291/original/015050100_1755231247-5.jpg)