TEMPO.CO, Jakarta – A recent study in mice suggests that microglia, immune cells found in the brain, may play a role in early memory loss, or infantile amnesia. The findings, published in the journal PLOS, strengthen the view that forgetting is not simply a brain failure, but rather part of an active process during development.

Research led by Erika Stewart of the School of Biochemistry and Immunology at Trinity College Dublin, Ireland, found that reduced microglial activity in infant mice enabled the animals to retain memories of frightening experiences longer than normal. This suggests that the developing brain actively regulates which memories remain accessible.

Infantile amnesia is a nearly universal phenomenon in humans, where early life experiences are not stored as long-term episodic memories. While individuals can learn skills and form emotional associations early on, memories of specific events are generally difficult to recall in adulthood.

In the developing brain, microglia not only function as defense cells but also play a role in shaping neural circuits by pruning synapses and influencing the maturity of neural networks. Because memory relies on neural connections being strengthened or pruned, microglia are thought to potentially influence whether a memory remains accessible as the brain grows.

“Microglia, the resident immune cells of the central nervous system, can be thought of as ‘memory managers’ in the brain,” Stewart said, as quoted in an Earth report on January 22, 2026.

To test this role, researchers conducted a fearful experience-based learning experiment in infant mice. In adult mice, such experiences typically produce long-term memories. However, in infant mice, these memories typically fade quickly. When microglia were inhibited, the infant mice showed stronger recall abilities than would normally be expected at that age.

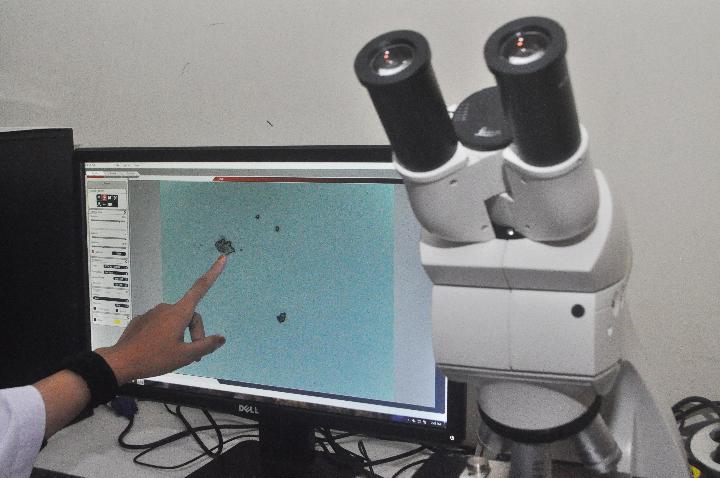

The researchers also observed microglia activity in two brain regions closely linked to memory and emotion: the dentate gyrus in the hippocampus and the amygdala. Decreased microglia activity in these two areas corresponded with an increase in the mice’s ability to retrieve memories.

In addition, the study examined engram cells, the neurons that form part of the physical trace of a memory. Using luminescent markers, the researchers found that inhibiting microglia made engram cells more active, indicating that memory networks are more easily reactivated.

“Our paper highlights their specific role in infantile amnesia, and suggests that similar mechanisms may exist between infantile amnesia and other forms of forgetting, both in everyday life and in disease,” Stewart said.

These findings also correlate with previous research in mice born to mothers with activated immune systems. In that study, the offspring of these mice did not display the normal pattern of infantile amnesia. However, when microglia were inhibited, the pattern of infantile amnesia reappeared, strengthening the suggestion that microglia play an active role in forgetting early in life.

Research team member Tomás Ryan, also from Trinity College Dublin, considers infantile amnesia to be the most common, yet often overlooked, form of memory loss. According to Ryan, infantile amnesia may be the most universal form of memory loss in the human population.

“Most of us don’t remember anything from the early years of life, despite experiencing so many new experiences during this formative period,” he said. "This is a neglected topic in memory research, precisely because we all accept it as a fact of life." Ryan also raised the possibility that early memories are not erased, but rather stored differently.

Although this finding has only been conducted in mice and cannot yet be directly applied to humans, it is thought that this finding opens up new research directions for understanding how microglia form memory networks during brain development. "It will be interesting and important to identify humans who do not experience infantile amnesia, to study how their brains work and understand their experiences in early childhood education," Ryan said.

Read: US Couple Welcomes Baby from 30-Year-Old Frozen Embryo

Click here to get the latest news updates from Tempo on Google News