RESEARCHER and economics lecturer from the Islamic University of Indonesia (UII), Listya Endang Artiani, stated that there is a striking imbalance in the import tariff agreement between Indonesia and the United States, negotiated by President Prabowo Subianto with U.S. President Donald Trump. According to Listya, the agreement tends to favor the U.S. rather than being mutually beneficial.

"One of the most crucial aspects of the trade agreement between President Prabowo and U.S. President Donald Trump is the imbalance in the agreed tariff structure," Listya told Tempo in a statement on Friday, July 18, 2025.

Prabowo, through his Instagram post on Wednesday, June 16, 2025, admitted to negotiating with Trump over the phone. Following Trump's announcement in early April regarding reciprocal import tariffs with U.S. trading partners, Indonesia was initially subjected to a 32 percent import tariff. Now, Prabowo's lobbying has reportedly resulted in a reduction of Indonesia's import tariff to 19 percent.

However, this negotiation comes with conditions. Import tariffs from the U.S. to Indonesia, on the other hand, will become 0 percent, or tariff-free.

Moreover, through his platform Truth Social on Tuesday, July 15, 2025, Trump stated that Indonesia agreed to purchase energy from the U.S. worth US$15 billion, agricultural products worth US$4.5 billion, and 50 Boeing aircraft, mostly Boeing 777s.

Imbalance in the Agreement: Who Actually Benefits?

According to Listya, at first glance, this agreement appears to be a positive achievement, potentially boosting the competitiveness of Indonesian products in the U.S. market. However, upon closer examination, a very striking imbalance emerges: products from the United States will enter the Indonesian market without tariffs and non-tariff barriers.

"In terms of international trade, this is no longer a mutual symbiosis, but rather it resembles a one-way street," said the lecturer from the Faculty of Business and Economics, UII, Yogyakarta.

Listya explained that such a tariff scheme creates a high-risk trade asymmetry for the national economy. This is because with full domestic market access granted to products from advanced countries like the U.S., Indonesia's domestic industry, which in many sectors is still in a growing phase, will face very heavy competitive pressures.

Products from the U.S., produced with large economies of scale, high technology, and implicit government subsidies, are likely to be sold at lower prices with higher quality compared to local products. In the theory of competitive advantage, this constitutes an "unfair playing field" when two players compete in an unequal arena.

According to Listya, a situation like this has the potential to trigger a phenomenon referred to by Dani Rodrik, a Harvard economist and critic of neoliberal globalization, as 'premature deindustrialization.'

Rodrik stated that developing countries tend to experience the regression of their manufacturing sector even before the sector reaches its optimal capacity.

In Indonesia's context, she said, if domestic manufacturing products are displaced by tariff-free U.S. imports, the absorption of labor, technology transfer, and the development of domestic supply chains will be disrupted. Consequently, the process of structural transformation, the transition from a resource-based economy to an industrial and innovation-based economy, may stagnate or even reverse.

Additionally, from the terms of trade perspective, the ratio between Indonesia's export and import prices could actually deteriorate. While the decrease in export tariffs to the U.S. does provide opportunities for increased export volume, this will only have a significant impact if Indonesian products have high added value and elastic demand.

If the increased exports consist of primary commodities or raw products, their economic value is low, and dependence is high. Meanwhile, tariff-free U.S. products tend to be high-value items: pharmaceuticals, medical equipment, digital technology, industrial machinery, and subsidized agricultural products. Consequently, Indonesia could experience deteriorating terms of trade.

"We would have to export more just to import critical commodities at higher prices," she said.

According to Listya, from the perspective of international law and norms, this agreement substantially violates the principle of 'reciprocity,' which is the foundation of the multilateral trade system under the GATT/WTO. This principle demands a balance of benefits between countries entering into trade agreements.

In this context, she said, Indonesia appears to be sacrificing its domestic market protection without receiving comparable concessions from the U.S. This condition not only weakens Indonesia's bargaining position in the global forum but also sets a detrimental precedent for future trade negotiations.

In the theory of international trade, such an agreement is also susceptible to driving trade diversion, which involves diverting trade from more efficient trading partners to politically favored countries. For example, Indonesia might start importing corn from the U.S. because of the tariff exemption, even though corn from ASEAN countries might be cheaper and more efficient.

"This will actually damage the economic integration of the region and reduce the potential benefits of regional trade agreements such as the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) or RCEP," Listya said.

The next implication is related to the current account balance. If exports do not grow as fast as imports from the U.S., Indonesia's current account deficit could widen. In the medium term, this will pressure the rupiah exchange rate, trigger capital outflows, and increase dependence on external financing such as foreign debt.

"This is reminiscent of the balance-of-payments crisis experienced by Asian countries during the 1997-1998 crisis, when trade and financial liberalization were implemented without strong macroeconomic protection and control," she said.

Overall, according to Listya, this tariff scheme raises fundamental questions: Who actually benefits? Will the people of Indonesia, local industries, and workers directly benefit? Or is it just a handful of large importers and distributors of U.S. products who enjoy the surge of profits from trade barriers being lifted?

Without protective regulatory mechanisms (safeguard measures), adaptive subsidies, and a roadmap for strengthening the competitiveness of the national industry, this agreement is not a strategy but rather a fragile openness. In other words, an agreement that superficially appears to be a diplomatic victory could become an economic time bomb if not managed carefully.

In the theory of sustainable development, every trade policy should be linked to the domestic ability to adapt and grow. Trade diplomacy is not just about a 'deal,' but about how each agreement strengthens the national economic structure, protects the workforce, and creates inclusive long-term benefits.

"Without this, we are only digging the pit of inequality with our own hands," Listya concluded.

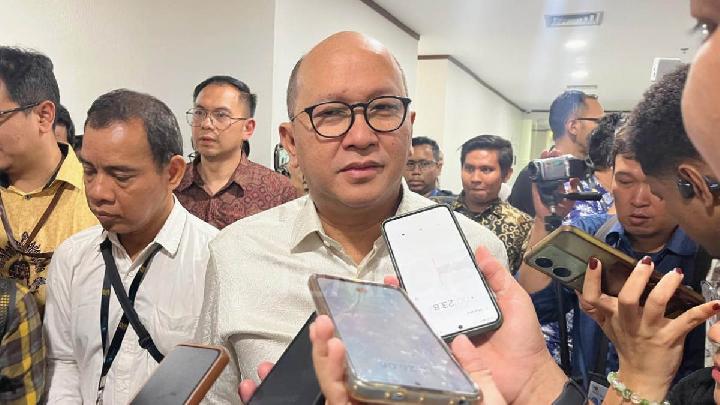

Prabowo previously said that all negotiations with Trump have been calculated for their impact by the government. The head of state claimed that the government indeed needs to import energy and agricultural products from the U.S. In addition, the government also needs to expand Garuda Indonesia because the airline is a national pride for Indonesia.

"We also must think about what is important to me, which is my people. What is important is that I must protect our workers," Prabowo said at Halim Perdanakusumah Air Force Base, Jakarta, on July 16, 2025.

Eka Yudha Saputra contributed to the writing of this article

Editor's Choice: Economists Warn of Trade Deficit Risks Following Trump-Prabowo Tariff Deal

Click here to get the latest news updates from Tempo on Google News

:strip_icc():format(jpeg)/kly-media-production/medias/1407603/original/079705400_1479294075-Ali_Khamenei.jpg)

:strip_icc():format(jpeg)/kly-media-production/medias/5258672/original/007662100_1750394658-18b4e792-fa49-48cf-b166-455eb3a3b632.jpg)

:strip_icc():format(jpeg)/kly-media-production/medias/4134468/original/062773800_1661335557-Makam-Mahligai-Barus-sumutprov.go.id_3.jpg)

:strip_icc():format(jpeg)/kly-media-production/medias/3657996/original/085161000_1639046078-minnie-zhou-0hiUWSi7jvs-unsplash__1_.jpg)

:strip_icc():format(jpeg)/kly-media-production/medias/1370182/original/075242200_1476146517-1237792244044309032.jpg)

:strip_icc():format(jpeg)/kly-media-production/medias/5262371/original/036341300_1750742555-WhatsApp_Image_2025-06-24_at_12.18.10.jpeg)